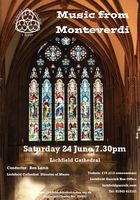

Music from Monteverdi ()

Celebrating 450 years since the birth of Claudio Monteverdi, our summer concert will be a selection of works by the composer and his contemporaries. Spanning Renaissance and Baroque, Monteverdi was an inventive composer, developing new styles of composition.

- Cantate Domino: Monteverdi

- Adoramus te, Christe: Monteverdi

- Nulla in mundo pax sincera: Vivaldi —

- Aria: Nulla in mundo

- Recit: Blando collere

- Aria: Spirat anguis

- Alleluia

- Magnificat: Buxtehude

- from Selva Morale et Spirituale: Monteverdi —

- Laudate Pueri

- Magnificat

- Laudate Dominum

- Beatus Vir

We sang:

- Magnificat anima mea Domine — Buxtehude

- Adoramus te, Christe, SV289 (1620) — Monteverdi

- Beatus vir (1630) — Monteverdi

- Cantate Domino, SV292 (1615) — Monteverdi

- Selva morale e spirituale, SV 252–288 (1641) — Monteverdi

- Nulla in mundo pax sincera, RV 630 (1735) — Vivaldi

Venue

Lichfield Cathedral, The Close, Lichfield, WS13 7LD [map]

« Come and Sing Favourite Opera Choruses (May 2017) ‖ French Trip concert at Amiens (Jul 2017) »

Reviews

Review of June 2017 Monteverdi concert

One of the benefits of celebrating the anniversary of a composer is the opportunity to make the acquaintance of less familiar music, and it may be that quite a few in both choir and audience had their first real introduction to the great Monteverdi in the Cathedral on Saturday, when conductor Ben Lamb steered the Lichfield Cathedral Chorus through a cross-section of his music along with his musical descendants Buxtehude and Vivaldi. This programme, celebrating Monteverdi’s 450th birthday, was a masterful microcosm in one evening of the amazing transition from Renaissance to Baroque.

Perhaps this was unwittingly exemplified by the fact that the audience instinctively felt it wasn’t quite appropriate to clap after the first two motets, both of which ended firmly in the Old Style which Monteverdi tried valiantly to adopt in his earlier compositions, despite his constant urge to lighten both texture and rhythm. After this we were treated to the most delightful performance of a high baroque Vivaldi motet for Soprano (Hannah Grove), and on this occasion two violins and basso continuo. The clarity and richness of Hannah’s voice, the crispness of the two violins, Joanna Park and Maria Oguren, and the sensitivity of the basso continuo — Alexander Woodrow (organ) and John Parsons (cello) — combined to create a perfectly balanced performance, which in the final masterfully executed Alleluia brought a smile to many faces in the attentively listening choir.

This was followed by a magnificent Magnificat, attributed to Buxtehude, who fits neatly between the other two composers. This work was so different from the solid organ works by which Buxtehude is more generally known; it has a lightness of rhythm, is in triple time throughout and uses much contrast of soloists and full voices, all features derived from the influential Venetian school. Here Hannah was joined by well-matched mezzo Ailsa Cochrane, the lovely warm, balanced tenor Robin Morton and the fine clear, crisp Italianate singing of tenor Nicholas Berry, who not only sounded but also looked the early Baroque part…I could imagine him swaggering into St Mark’s Square, Venice in his doublet and hose! Bass Simon Gallear also gave a rounded, deceptively smooth performance of his quite instrumental line. The choir settled into this work, although it initially lacked the underlying sense of pulse required to draw out the rhythmic subtleties, perhaps because of the sheer weight of numbers singing.

This was indeed one of the main difficulties for the choir throughout the evening. Monteverdi’s forces would have been far smaller, and almost certainly would have been separated in the different galleries of St Mark’s, coming together in “big moments” as the original quadrophonic sound. The quickness of the rhythmic figures and the lightness of touch needed in the choral parts were almost impossible to achieve with such huge forces, though on this occasion the tenors benefitted from their slightly smaller group size, and came across with a refreshing spontaneity, accuracy and vigour. The choral sound was magnificent in moments such as the big chords in the brisk performance of Beatus Vir, but sadly the split-second accuracy needed for the devilish “irasceturs” and similar spots was not quite achieved. Volume was never going to be a problem with the wise instrumentation chosen for these works; it might all have benefited from the choir reducing their attempt to sing loudly and concentrate more on a lighter, more speech-like delivery.

But for all that it was wonderful to hear all of this magnificent music performed with such verve and enthusiasm, and it would be good to think that many people have gone away wanting to hear and find out more about this fascinating period in music history. Perhaps when we flock to the Messiah at Christmas we will be able to think back to this experience of what had gone before Handel’s achievement, and marvel.

Megan Barr, June 2017